Browsing in the Stanford Bookstore several years ago I stumbled across the anthology Philosophy After Darwin edited and introduced by the philosopher Michael Ruse. Some of the older readings such as excerpts from the work of Herbert Spencer and G. E. Moore (one of the many critics of Spencer’s absurd idea that we should try to estimate where Darwinian evolution is headed and then make an effort to help it along) were familiar and expected from what I knew of philosophy. But I was surprised to see excerpts from Charles Darwin himself and even more surprised to see excerpts from the well-known American philosophers John Dewey and William James. Dewey and James were not very familiar to me, but I would have guessed they wrote about zero words on the topic of the relationship between Darwinian evolution and philosophy. And who were these other writers such as Chauncey Wright? Why was this anthology so long? What was going on here? Is this really a live area of debate in modern philosophical circles?

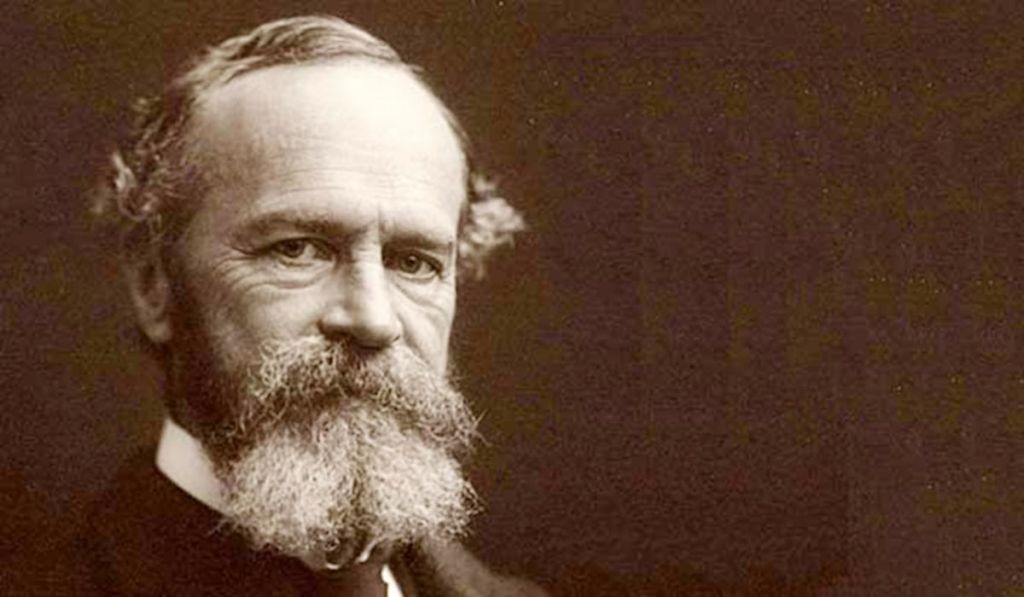

As I skimmed Ruse’s introduction I learned that William James (1842-1910) in particular was “an ardent Darwinian” whose textbook Principles of Psychology was infused with Darwinian explanations and “In fact, there were complaints by James’s students at Harvard that he was a bit obsessive on the subject” of Darwinism. This was so utterly at odds with the little I thought I knew about William James (the guy interested in parapsychology and religion?) that I immediately bought Ruse’s book and started to do some research.

The first thing I discovered as I read through William James’ writings (not just the bits in Ruse’s anthology) was that the real William James bore almost no relationship to what I thought I knew about William James from popular culture. He was, for instance, not a mystic or a skeptic who denied the possibility of human knowledge of external reality. He was in fact a hard-boiled Empiricist working in the tradition of Locke and Hume and J. S. Mill and the other British and Scottish Empiricists. Yes he was trying to correct a deficiency in classical Empiricism by being more realistic about the nature of the very finite and imperfect biological human beings who are the “subjects” that are doing the observing of the objects around them, but James is clearly in that tradition. He dedicated his book Pragmatism to the memory of J. S. Mill for heaven’s sake.

The second thing I discovered as I read is that William James seemed to continually stay on a productive track in his writing. Again and again he seemed to take intriguing angles and ask interesting questions and develop compelling answers – no matter what the topic from morality to epistemology – because of his grounding in evolutionary biology. In contrast to some other philosophers, James seemed to always have true north locked in because he had in his mind at all times a clear and honest picture of the human actors he was writing about and for. I think the following passage from his chapter on Philosophy in his book The Varieties of Religious Experience illustrates this:

“The Continental [non Empiricist] schools of philosophy have too often overlooked the fact that man’s thinking is organically connected with his conduct. It seems to me to be the chief glory of English and Scottish thinkers to have kept the organic connection in view. The guiding principle of British philosophy has in fact been that every difference must make a difference, every theoretical difference somewhere issue in a practical difference, and that the best method of discussing points of theory is to begin by ascertaining what practical difference would result from one alternative or the other being true. What is the particular truth in question known as? In what facts does it result? What is its cash-value in terms of particular experience?”

What I hope to do on this page is collect the insights that I’ve gained from my study of William James. For me, put off by the oversimplifications and caricatures of popular culture and glib summaries written by those who should have known better, it was truly a lucky accident that I ever realized the pathbreaking work that William James did in philosophy and other fields. It should not require a miracle for someone to be aware of the important contributions that he has made to these fields, and I hope writing this blog helps out in some small way in that regard.

The essay just below – William James and Evolutionary Psychology – summarizes some insights I’ve gleaned from the writings of William James and related writers such as John Dewey and Chauncey Wright in an area that is today called evolutionary psychology. At the end is a list of suggested reading for someone interested in doing further reading in this area.

The next essay deals with moral philosophy. I’m not sure how to describe the sad state of of moral philosophy as an academic field. The subject seems to have gone backwards since the early part of the 20th century. Today, many academic philosophers seem to avoid the subject as a professional embarrassment and some sort of mug’s game. Although William James wrote only a couple of articles directly on the topic of moral philosophy, the bits he did write were directed at shoring up the foundations of moral philosophy and making it more constructive and were my primary inspiration for the idea in the essay just below titled A Plea For Commonsense in Moral Philosophy. (Updated slightly on April 21, 2024 mostly to clarify how my proposal relates to Utilitarianism. Updated on June 25, 2024 to add a reference to Elizabeth Anscombe’s 1958 paper Modern Moral Philosophy.)

I further updated the essay above on August 2, 2025 to (i) clarify within the essay itself that the work of WiIliam James including, especially, his 1891 journal article “The Moral Philosopher and the Moral Life” was my inspiration for writing the essay, (ii) compare what I propose in this essay to the approach to moral philosophy taken by a subgroup of Utilitarians known as Preference Utilitarians, and (iii) add a reference to Peter Singer’s 1994 anthology Ethics, which includes a long excerpt from James (1891) as the leading example of Preference Utilitarianism (before the term was coined) because of its emphasis on the satisfaction of the preferences of individuals.

<end>